Philip Roth Goes Home Again

Philip Roth Goes Home Again

Philip Roth, a prize-winning novelist and frequent Esquire contributor, died Tuesday night at the age of 85. In 2010, on the occasion of his thirty-first book, Esquire's Scott Raab returned to the Newark of Roth's boyhood. And there, on Philip Roth Plaza, he couldn't stop laughing.

Scott Raab

May 22, 2018

This story first appeared in the October 2010 edition of Esquire.

There are worse places to be stuck in traffic than midtown Manhattan, worse people to be stuck with than Philip Roth. It's pretty nice, actually: Esquire hired a car to schlep us to New Jersey, Roth's old Jewing grounds, a jet-black SUV with a name — Tahoe? Denali? HinduKush? — and backseat as big as all outdoors, icy air-conditioning, and a small man at the steering wheel.

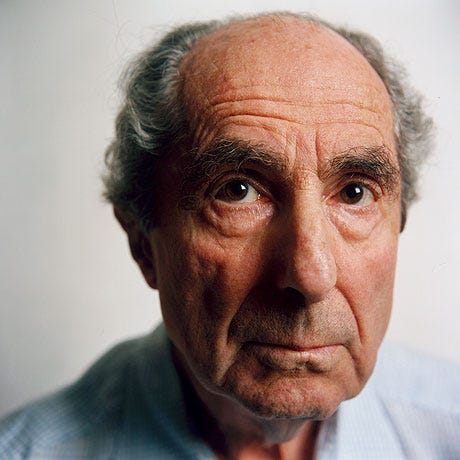

Roth's reputation, especially when it comes to stuff like doing publicity, is daunting. He is severely smart. Suffers fools badly. Parries, rather than answers, questions.

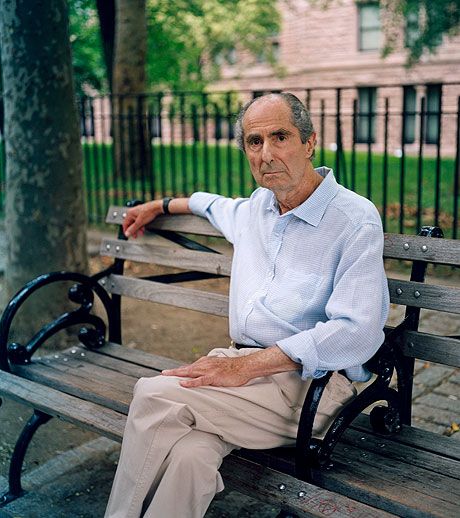

True, true, and true. Roth has the mien and bearing of a man in charge by dint of brainpower alone. He is tall and thin, hawkeyed, comfortable in silence. He takes words in — visibly takes their measure — with no more than a cock of an eye or a narrowed brow. Say something particularly insipid and he may purse his lips.

And how else would anybody but a fool meet the world? This is no celebrity. This is a poker-faced novelist, a man who tasted fame, gagged, and spit it out, the same man who two-plus decades back told an interviewer, "I am very much like somebody who spends all day writing."

Not today. Today we're Newark-bound, and to break the ice, I've brought the master a gift. It's a copy of the New American Review containing perhaps the worst thing Roth has ever published, a long short story titled "On the Air."

"Wonderful!" Roth says. "I don't have it."

You do now.

"I hate that story."

I'm not so fond of it myself.

"I was experimenting with excess. You know what that's like? I just wondered how far I could go, and I discovered what my limit was."

***

Roth's talking about his reading these days, revisiting a revered Russian master of the nineteenth century, Ivan Turgenev.

"Fathers and Sons is a great book — there's a new translation of it. I think it's called Fathers and Children now, and the translation is wonderful. And there are several long short stories that are pearls. One is called 'The Torrents of Spring' or 'Spring Torrents,' which is a masterpiece, and the other — which is beyond masterpiece — is called 'First Love.' Read those two things."

Roth chortles with something like delight. He stopped teaching twenty or so years ago but still seems as if he'd fit in on any campus in any decade. It's not only his outfit — tan slacks, blue-and-white-checked shirt with the sleeves rolled loosely up his skinny forearms, brown walking shoes — but also his easy passion for those writers who've nourished his soul.

I mention Joseph Conrad, whose clinical eye, deceptive clarity, and long, loping rhythms remind me of Roth's own.

"He's a pure powerhouse. I recently read a biography of him that's kind of interesting, too, an English biography. There's also Conrad's great short novel, which I hadn't reread since I was in my twenties, The Nigger of the Narcissus. It's an absolute masterpiece. Beyond belief. And about race, it's brilliant. So brilliant. Conrad is rich. He's very rich."

Again with the chortle. To feast so deeply upon words, it says, is luscious beyond words, a way of being in the world while being free of the world's whims, and a way of knowing humanity free of the mess of humans. It is rich, very rich — a schoolboy's love rather than a scholar's.

"I've enjoyed teaching — not teaching writing. I taught literature at the University of Pennsylvania, and I liked that very much. It was a great way of getting out of the house, of not being stuck alone in my room all day, and, as I have Lonoff say in The Ghost Writer, I got to use a public urinal — that was a breakthrough — and also I got to read a lot. That was the best of it — I got to read and think about books and study books. My education comes from teaching, really."

"Hey," the driver says, "you want to try the Howen Tunnel?" English is not his first language.

"What?"

"Howen."

"Holland Tunnel," Roth echoes. "Why? Is this no good?"

"Yah. See — not moving."

"You don't think we can get from here to the Lincoln Tunnel in a few minutes?"

"No."

"No?"

"No."

"Then let's go downtown."

"Could be half hour maybe."

"Let's go downtown."

"Not moving."

"Let's go downtown."

"All right."

"We're going to do this interview in Chinatown," Roth tells me.

"No," says the driver. "I not going Chinatown."

Roth's gusting laughter fills the SUV.

"Just tell them about how I wrote about Chinatown," he roars. "Just set the whole thing there."

***

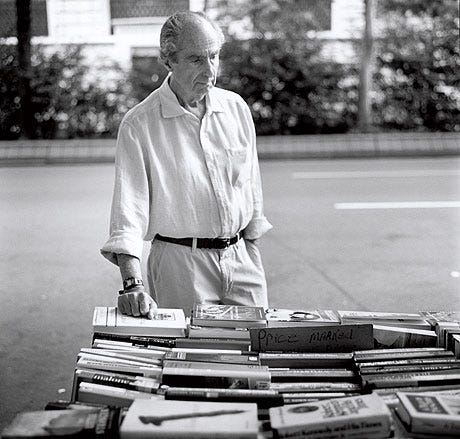

Roth is both powerhouse and plow horse. His new book, Nemesis, is his thirty-first; he has published eight novels in the past ten years. He was a twenty-seven-year-old wunderkind in 1960, when Goodbye, Columbus won the National Book Award; in 1969, Portnoy's Complaint earned him both a fortune and — thanks to its uninterrupted 274-page monologue, the comic confessions of a serial masturbator — a gossip-column fame that lingered even as Roth himself fled from public view; in 1979, he gained a literary second wind with the creation of Nathan Zuckerman, the narrative voice of nine novels — including American Pastoral, which won the Pulitzer prize in 1998. Roth's currently working on book thirty-two.

"It could be outdated" is all he'll say about it.

You really think so?

"I don't think so, nah. No. But I have a lot of work to do."

Hard to believe, but the man is seventy-seven years old now. The survivor of two childless marriages, wed only to the word, Roth has outlived a slightly older cohort of Jewish-American writers — biased I no doubt am, but has any other American ethnic group boasted a top-of-the-order to match Malamud, Mailer, Roth, Bellow, and Heller? — and continues to outpace his few living peers. Every year I wait for the worthies of the Swedish Academy to come to their senses and bestow upon Roth the Nobel Prize in Literature; they never have.

Forgive me, I say, but with the Nobel, every year on the announcement day I grind my teeth.

"Oh, yes?" he says, entirely noncommittal, like a physician waiting for a patient to describe his symptoms further.

Every year I wait to hear them speak your name. So — is this a day that you're even aware of?

"No, it isn't," he says. Then he pauses. "I try not to be aware of it."

Someday. After they've made amends to each and every possible political constituency across the globe, your day may come.

"After the Trobriand Islanders," Roth shrugs, and laughs.

The traffic heading to the Holland is less heavy, but not much. Roth, bless him, doesn't complain. I sneak one long sideways peek at his nose: a classic Ashkenazi beak, a scimitar of flesh, the sort of schnozzle that put the rhino in rhinoplasty.

You and I go back many years, I finally say.

"Is that right? Where do we go back to?"

To 1969. To Portnoy.

"Oh, yes? How old were you in 1969?"

Seventeen. I was certainly fine with masturbating by then, but the idea that a writer was free to write anything — anything — any way he wanted had never dawned on me.

"Oh, yes?"

Ronald Nimkin's suicide. On page 98, Portnoy says, "My favorite detail from the Ronald Nimkin suicide" and then riffs for another twenty-two pages about the cage of love and guilt built for him by his parents' love and need before supplying that detail — a telephone message that fifteen-year-old Ronald had pinned to his shirt for his mother to find with his corpse.

"Now," Portnoy asks, "how's that for good to the last drop?"

That a serious writer could be so terrifyingly funny, could just let it rip — and could leave the reader himself hanging through five thousand howling words — all this was a huge revelation to me.

"I let it rip," Roth says. "I had written three books prior that were all careful in a way. Each was different from the other, but they didn't let it rip, and now was my chance. It was written at the tail end of the sixties, so all that was happening around one, and I was living in New York at the time, so the theatrics around me gave me confidence."

You were quite the bon vivant.

"No, no. I knew some interesting guys in the sixties — it was hard not to. I had a friend who had a strong influence on me, not as a writer, just as a friend. I was very fond of him; he was a terrific live wire — Al Goldman. He taught at Columbia. He wrote a classical-music column. He was very much a serious literature professor.

"The sixties transformed him. I don't know anyone more transformed — and many people were transformed. Al became a rock-music critic for Life, and he was my rock instructor. He used to take me to Madison Square Garden when he was covering various people.

"B. B. King came to the Garden, and Al took me backstage to meet him just after Portnoy's Complaint came out. The girls were lined up around the block for B. B. King's dressing room, and in back with him he had a half a dozen or so acolytes in powder-blue suits, and we sat around and talked for a while. Then I went to get the seat while Al interviewed him further — and when I left, B. B. King looked at his boys in their powder-blue suits, rubbed my seat, and said, 'This guy just made a million dollars from writin' a book.'

"I went to a Janis Joplin concert with him, I went to a Doors concert with him — it was wonderful. He knew everything — he could educate me. It was all brand-new to me."

Somehow, though, I can't see you as a guy diving headlong into the sixties. I can't imagine Philip Roth getting high.

"I didn't get high, no. I was — one was delighted by the theatrics of the sixties. I'd come out of the fifties, and we didn't have these theatrics."

You were an observer.

"I guess you would say that. I wouldn't become a member of that generation. I was a member of my generation. It was just all new to me, and Al knew everything about it. He died, poor bastard. Dropped dead on an airplane going to London, and his body was held in a refrigerator at Heathrow."

How long did he spend in the cooler?

"He was there a couple of days, because they had to do something about getting his body out and back to America. He had only paid for his way over."

Nothing about this sounds snide, much less ironical, coming from Philip Roth. These are the mere grace notes that go with manhood's end, the smaller details of the inevitable and often absurd catastrophe that fetches a man from wherever he stands and delivers him to oblivion's gate.

"Luckily he had a girlfriend with him," Roth adds after a moment.

For such things, Roth truly has a jeweler's eye.

"How could a street as modest as ours induce such rapture just because it glittered with rain?" he wrote in The Plot Against America. "How could the sidewalk's impassable leaf-strewn lagoons and the grassy little yards oozing from the flood of the downspouts exude a smell that roused my delight as if I'd been born in a tropical rain forest? Tinged with the bright after-storm light, Summit Avenue was as agleam with life as a pet, my own silky, pulsating pet, washed clean by sheets of falling water and now stretched its full length to bask in the bliss.

"Nothing would ever get me to leave here."

He left — for Bucknell and for the University of Chicago, for the Upper West Side and for a Revolutionary-era farmhouse in Connecticut, for a life in American letters without parallel. He left, but he took all this with him, and there is splendor, comic and otherwise, in savoring what remains — of Summit Avenue and of its prodigal son who has always remembered to forget nothing.

"They've got a plaque, too," Roth says, walking a few steps to 81 Summit, the second home from the corner. The patch of lawn behind the chain-link fence needs trimming. The first floor of the house is clad in faux-stone siding, the second in a faded yellow. Five narrow first-floor windows face Summit, each behind a grate whose black bars match the railings on either side of the redbrick stoop. The windows are set in a three-two arrangement and in the middle, screwed into the original wood beneath the siding, sits a square tablet.

HISTORIC SITE

PHILIP ROTH HOME

Below, in an eleven-line précis of his career, the plaque notes that the Roths lived on the second floor until 1942.

"Whaddaya think of that, huh?" Roth wants to know.

What do you think?

"I think it's great. The woman whose house this is is named Mrs. Roberta Harrington. She's a very nice lady; I'd like if she would come outside and talk. When they held the ceremony about four years ago, Mrs. Harrington got all dressed up and she came to the stairs there and I went over to say hello to her, to shake her hand, and she said, 'Step up here and give me a kiss.' We had a reception at the branch library and she was with me for the rest of the day."

The front door is shadowed by an eave, but some motion there catches Roth's eye.

"Maybe that's her," he says, approaching the stoop. "I hope she's alive."

Roth walks up the five steps to the front door, which is pushed halfway open by a strapping fellow who might be in his thirties.

"Hi," Roth says. "Is Mrs. Harrington home?"

"I believe she is, yeah," answers the fellow at the door.

"Would you tell her that Mr. Roth is here?"

The younger man fairly beams. "Mr. Roth," he says, "how are you?"

"Good. Did I meet you last time?"

"No, you didn't. But I know all about you."

"Oh, yeah?" Roth says brightly.

"I certainly do." And with that, he raps on the door to Mrs. Harrington's flat and she appears a few moments later, very much alive, in a sleeveless white blouse and white slacks, a brown head scarf knotted low on her forehead.

"How could a street as modest as ours induce such rapture just because it glittered with rain?" he wrote in The Plot Against America. "How could the sidewalk's impassable leaf-strewn lagoons and the grassy little yards oozing from the flood of the downspouts exude a smell that roused my delight as if I'd been born in a tropical rain forest? Tinged with the bright after-storm light, Summit Avenue was as agleam with life as a pet, my own silky, pulsating pet, washed clean by sheets of falling water and now stretched its full length to bask in the bliss.

"Nothing would ever get me to leave here."

He left — for Bucknell and for the University of Chicago, for the Upper West Side and for a Revolutionary-era farmhouse in Connecticut, for a life in American letters without parallel. He left, but he took all this with him, and there is splendor, comic and otherwise, in savoring what remains — of Summit Avenue and of its prodigal son who has always remembered to forget nothing.

"They've got a plaque, too," Roth says, walking a few steps to 81 Summit, the second home from the corner. The patch of lawn behind the chain-link fence needs trimming. The first floor of the house is clad in faux-stone siding, the second in a faded yellow. Five narrow first-floor windows face Summit, each behind a grate whose black bars match the railings on either side of the redbrick stoop. The windows are set in a three-two arrangement and in the middle, screwed into the original wood beneath the siding, sits a square tablet.

HISTORIC SITE

PHILIP ROTH HOME

Below, in an eleven-line précis of his career, the plaque notes that the Roths lived on the second floor until 1942.

"Whaddaya think of that, huh?" Roth wants to know.

What do you think?

"I think it's great. The woman whose house this is is named Mrs. Roberta Harrington. She's a very nice lady; I'd like if she would come outside and talk. When they held the ceremony about four years ago, Mrs. Harrington got all dressed up and she came to the stairs there and I went over to say hello to her, to shake her hand, and she said, 'Step up here and give me a kiss.' We had a reception at the branch library and she was with me for the rest of the day."

The front door is shadowed by an eave, but some motion there catches Roth's eye.

"Maybe that's her," he says, approaching the stoop. "I hope she's alive."

Roth walks up the five steps to the front door, which is pushed halfway open by a strapping fellow who might be in his thirties.

"Hi," Roth says. "Is Mrs. Harrington home?"

"I believe she is, yeah," answers the fellow at the door.

"Would you tell her that Mr. Roth is here?"

The younger man fairly beams. "Mr. Roth," he says, "how are you?"

"Good. Did I meet you last time?"

"No, you didn't. But I know all about you."

"Oh, yeah?" Roth says brightly.

"I certainly do." And with that, he raps on the door to Mrs. Harrington's flat and she appears a few moments later, very much alive, in a sleeveless white blouse and white slacks, a brown head scarf knotted low on her forehead.

"Hi, how are you?" she says.

"Hi," answers Roth. "How are you?"

"Good, good, good." Her face is like an old catcher's mitt, round and seamed, but the flesh of her arms is firm and her fingernails are bright red. For a couple of gnarled Newarkers circlingeighty, Mrs. Harrington and Mr. Roth look terrific.

"I was showing this gentleman how you're taking care of my plaque."

"I'm doin' the best I can with it. Excuse my yard, because I haven't got it cut yet."

"You look good."

"Thank you. I'm tryin' to keep myself up."

"It's nice to see you."

"It's nice to see you, too. So, are you just visiting?"

"Yeah. We're just visiting to take a look at it. Anybody ever come to look at it?"

"Quite a few people."

"Is that right?" Roth asks. "Yeah?"

Mrs. Harrington strokes her chin and nods slowly. "Quite a few people stop and look around, yeah. Mmmm-hmmm."

"Very good," says Roth.

"Yes, yes, yes."

"Good."

"Mrs. Trudeau has been here, also."

"What was that?"

"Mrs. Trudeau. She's the lady that came before you to let me know that the plaque was gonna be put up."

"Oh," says Roth. "Del Tufo — Liz Del Tufo."

"I'd say about three weeks ago."

"Did you ever get somebody from the city to do something about your front yard?"

Mrs. Harrington looks at him ruefully.

"I never had no one to do anything for me in this house since they put the plaque up. They talked about it, but they never did it. They never did. Told me allllllll about what they were gonna do, but nobody came to my home."

Her plaint is muted, but she seems to have been working on it for a while.

"They told me that if I would let them put your plaque on the house, they would take care of my gardening."

"I remember that."

"But they never did. Maybe you could speak to them."

"I'll give Ms. Del Tufo a ring and tell her."

"I hope that you will."

"Okay," Roth says, entirely serious. "It's good to see you."

"It's nice to see you again, too," says Mrs. Roberta Harrington. "Sorry that my yard wasn't up to par. We've had quite a bit of rain."

"Anyway," Roth says when we're back on the sidewalk, "I used to sit on this stoop a lot."

Not a lot of room to throw a ball.

"Yes there is. You'd play aces-up out in the street. You'd throw the ball against the edge of the step and it bounces off into the street — single, double, triple, home run across the street."

Ever have a pet?

"Jews didn't have pets. On Summit, one guy across the street had a dog. It always seemed to me absolutely bizarre. I never was inside his house, so I didn't know what it would be like, but nobody else had a pet. It didn't even occur to me."

Down Summit we stroll, toward Chancellor Avenue — in Roth's day, the hub of neighborhood commerce, lined with small shops, now a wasteland, more or less, an urban desert abandoned except for a storefront chapel.

"There's now a stadium down at the end of the street, next to the grade school. There was no stadium in my day, just a big dirt field, which I use at the end of Nemesis, when Bucky throws the javelin."

Bucky Cantor is the new novel's central character, a twenty-three-year-old playground director and quintessential good boy whose courage, diligence, and unstinting rectitude turn out to be no match for a polio epidemic devouring Weequahic's young in the summer of 1944.

It's a harrowing book, I say to Roth. Relentless.

"Terrific. Thank you. I hope it's good."

Did you know anyone like Bucky?

"No. I really made him up. Figuring who was going to be at the center of this thing — whether it would be a parent, or nobody — I landed on a playground director. And that was a gift, because all the kids are there and he has to suffer with them all. All the children are his children."

And he considers them so.

"Yes. As I imagine a young playground director would."

What a noble Bucky he is.

"Yes," says Roth. "He is a noble Bucky. And he gets fucked."

His laugh is the laugh of a creator who has lived long enough — has himself seen and suffered enough — to face the inevitable. The mirth and mischief of earlier books seem long ago and far away. In Nemesis, as in most of his recent work, the human being is helpless, acted upon in awful ways by a cruel, indifferent universe.

"Yeah," Roth says. "I accept that. Even before the BP spill, I knew that. Life is one long BP spill. Trying to cap the well is what you have to do. People go around capping the well all the time. Then the next well. And the next."

Chancellor Avenue School, Roth's old primary school, is still standing, not far from Weequahic High, where he graduated at the age of sixteen.

"Let's go back to the playground," Roth says. "Then we'll come back out and try to go into the school."

When he sees that our path is blocked by a construction fence, Roth stands at its gate, gazing past the building.

"In fact, the playground doesn't exist," he says, still gazing. "It looks like they're building a parking garage."

"Mr. Roth," says Detective Santaniello, "did you know you always wanted to become a writer?"

"Not when I was a little one here. I went in the Army in 1955 or so, and then I began, at night there — I began to write stories."

Spotting a gap in the fence, Roth slips through, moving toward the back of the school.

"This was all playground," he says. "It was just a big open area for kids. Gone. Maybe it's for the best."

You think?

"That it's all for the best?" he says, still staring into the middle distance where the playground isn't. "Well, what can you do?"

Inside Chancellor Avenue School, it smells like floor wax and fish sticks. Sergeant Glover visits the school office to get us passes. Roth heads through the auditorium doors and stops, looking over the rows of empty seats to the dark stage.

"We came once a week and sang songs that supported the armed forces. In 1941 the war began; I was eight. When it finally ended, I was twelve, and we sat in here and we sang 'The Caissons Go Rolling Along,' and the Marine hymn — 'From the halls of Montezuma' — and the Air Force song."

And he breaks sweetly into "Off we go, into the wild blue yonder ..." and I join in on the "Climbing high into the sun... ."

"Very good," Roth laughs. "You want to sit down?"

After the auditorium, we visit the gym. A class of third- or fourth-graders is shouting and clapping in a cluster under a basketball hoop at the other end. Nobody pays any mind to Roth, who stays close to the doors, watching.

"It looks very much the same. The brickwork is the same. We had to do all that stuff in the ceiling — we had to climb those ropes. I hated it. I never liked the rope and the rings. And there used to be something called the pommel horse, where you did gymnastics."

I smell fish. You smell fish?

"It's Friday," Roth says. "You want to go next door to the high school?"

Visiting the high school turns out to be a bit of a production, even with Glover and Santaniello to get us past the metal detectors at the front door and with Roth's name and ancient yearbook photo on a black-and-white poster of the school's Hall of Fame inductees.

"What's your name again, sir?" The woman behind the counter in the school office is on the phone, trying to find someone to accompany us. Nobody — not even this mild-mannered Hall of Famer with two police in tow — prowls Weequahic High without a hall pass.

"Roth. R-O-T-H."

"He's just walking through the neighborhood," she tells whoever's on the phone with her. "He went to school here and at Chancellor, so he's just coming here to walk around."

Eventually, a vice-principal arrives to escort us, a perfectly nice woman who is particularly focused on showing off the school's "data room," an antiseptic, air-conditioned computer center entirely devoid of human life. Roth listens patiently — the cold air is delicious — as she rambles on. There are no students here, no evidence that any students ever have been here; the shelves and desks and chairs are carefully arranged, spotless; the room itself is cool, dark, and utterly generic; I can't imagine that anything in this building could possibly be of less interest to Philip Roth, and I suspect that no one here today has any firm idea who he is.

As we head back down the corridor, finally free, I see a yellow-and-black placard taped high upon the cream-colored wall:

NEMESI

ONE THAT INFLICTS

RETRIBUTION OR VENGEANCE

Up and down the hallway, similar placards with other vocabulary words and definitions look down at the rows of lockers. This one, however, is staring right at Philip Roth.

Look, I say, pointing.

"Aha," says Roth, laughing again. "Now we know what your opening is going to be."

At Hobby's Deli, in downtown Newark, Glover, Santaniello, and I get sandwiches. Roth orders the feta-cheese salad with grilled chicken and the house dressing, oil and vinegar.

Nobody gets the Russian dressing anymore.

"That used to be the most popular," Roth says.

Was it?

"Sure. I used to love it. It's made with ketchup and mayonnaise."

What was Thousand Island? Russian mixed with French?

"It's gone out of existence, Thousand Island dressing. But oil and vinegar will never die."

The waitress brings Roth the small dressing bottles along with his salad.

"I gotta do it myself," he says.

I'll do it for you, if you wish.

"No, no — I can do it. I'll get my strength back."

He looks at my sandwich.

"What have you got there? A little bit of everything."

I've got corned beef. Chopped liver. More corned beef. You want a taste?

"No, no."

You avoid the cold cuts?

"More or less."

One of the proprietor's sons comes over to say hello.

"How is your father?" Roth asks.

"Overall, he's well. They're adjusting his pacemaker a little bit — lube, oil filter. Overall, thank God. Just celebrated his eighty-seventh birthday."

"Tell him I send my best regards."

"I sure will. He'll appreciate that."

"We weren't expecting the Iraq salamis in the back," Roth says, pointing to the far wall where bunches of them hang from the ceiling above a sign proclaiming OPERATION SALAMI DROP. Hobby's, it turns out, has shipped twenty-seven tons of salami to U. S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, sustaining a tradition begun when eighty-seven-year-old Samuel Brummer — Hobby's owner since 1962 — was a soldier in Europe during World War II.

"His buddies in Newark would send him a salami every month," says the son, "and as soon as he got it, everyone in his unit knew it. My father would take out his bayonet and cut off a hunk, and everyone would share."

I wonder how they slice them now. I don't think they have bayonets anymore.

"They don't have bayonets?" Roth says. "Sure they have bayonets."

He chews fast. A little noisy. I ask him how the Army was for him.

"The Army? I learned to use a bayonet."

Attacking dummies?

"Yeah. We used to shout 'Kill' when we did it. I was twenty-one, I guess. You'd attack the dummy and yell 'Kill' and hit him with your bayonet. In the Army, you can do anything."

A soundless TV to our left is tuned to CNN. Birds coated with gunk fill the screen.

"It's a shame," says Santaniello.

"Extraordinary," Roth says. "Covered. Just covered. And dying."

What prompted you to join the Army?

"If I didn't join, I would've been drafted. I wanted to get it over with. The Korean War had ended, but the draft was still on, so I enlisted rather than wait to be drafted."

"They say it'll be coming up this way if they don't put a cap on it," says Santaniello.

"If it turns around the Florida hook," Roth says. "Who knows? Twenty-five years from now, one thing we know for sure — the oil will still be coming out. I can die now. I can die knowing something, for sure."

| [TAG3] |

| Philip Roth |

The titanic black SUV is waiting to deliver us back to Manhattan. Inside, an R&B ballad is playing softly and the air is thick with cologne.

"Something's been going on here," Roth joshes.

I ask the driver what he's been doing in the car.

"I waited outside."

I think you had a little party in here.

"Nonononono."

He's laughing. We're all laughing.

You're okay? I ask Roth. You ready to head back?

"Yeah."

This was all right?

"You willing to start again?" he laughs. "Do you want to do it all over again?"

Frankly, no. I'm exhausted.

He roars. "I know you want another shot at the computer lab," he says.

You're not tired?

"No."

You're fresh.

"I'm okay."

You're in good shape.

"I am in good shape," says Philip Roth, beaming.

God bless him. For years — many, many years — I've read about what fun Roth can be, a claim invariably undermined by a total lack of supporting evidence and inevitably buried beneath a ponderous discussion of a new Roth book and of Roth's work as a body. It's fantastic to see the man out and about, free of the peculiar calculus of being a literary figure, a shaman, a character upon whom readers and entire tribes — I'm looking at you, landsmen — have for half a century projected scrim after scrim of their own fear, neurosis, and plain old bullshit. Enough.

Read the books. The Newark wiseacre spitting out novels like a bachelor-party stripper firing Ping-Pong balls out of her snatch is seventy-seven years old now. Behold a master, treasure his work, and shut the fuck up. Just read the books.

You've brought me a lot of joy over the years, I gush.

"That's good," he says. "I'm delighted."

I had to say it, I say.

"I can take it," he says.

It's good that you didn't go to law school.

"It is," he says. "I think I would have had a coronary by now. I would have a family now who I never saw."

Has the writing gotten any easier?

"That's hard to answer. There are days and weeks that are very difficult. I've never been without the struggle. When I started writing, I did have false starts. I would write seventy-five, a hundred pages of something and toss it aside. I don't do that. I don't make false starts any longer. So that's an improvement.

"Who knows what'll happen in the next ten years. Maybe it'll get better. Maybe it'll get worse. I don't know. At this stage of the game, you don't know what's going to happen. You see different writers as they get old, what happens to them. Some shut down. Some write sporadically — the way Bellow did it.

"I have a slogan I use when I get anxious writing, which happens quite a bit: 'The ordeal is part of the commitment.' It's one of my mantras. It makes a lot of things doable."

Mine is from a fat relief pitcher, Bob Wickman: You gotta trust your stuff.

"That's very good. I used to have little things up over my desk at various times. One of them was 'Don't judge it.' Just write it. Don't judge it. It's not for you to judge it.

"I have four or five friends who I ask to read my final drafts and to say whatever they want to say to me about it. I put it through that sieve, and they tell me what they think about it, and then I consider it and make changes if it seems appropriate. Often it does. And there's an excellent copy editor at Houghton Mifflin, where I publish, a wonderful guy named Larry Cooper, and he goes over the thing very carefully and makes sure I don't make a schmuck of myself."

***

We're back through the Holland Tunnel and into the city.

"So what do you do now?" Roth asks. "Go back to the office?"

I'll go back and tell them it was horrible. I'll tell them you were very difficult and cranky.

"Tell them, 'All the guy wanted to do was go to the computer lab.' "

What do you do now?

"What do I do now?"

I need an ending.

"Oh, you need an ending. Well, the afternoon is cut short. I have to go see somebody in the hospital around five o'clock."

Oy.

"She's all right. She'll be all right. I have a plate full of mail which I should answer — I can do that in the next two hours. That's what I'll do."

You own a shredder?

"I have a shredder in Connecticut."

I love a shredder. A good shredder.

"Shredders are good," Roth says.

Some days I find a kind of comfort in shredding.

"Don't end it with my shredding. Just the computer room at Weequahic gives you a terrific piece. Keep me in the computer lab."

Better there, I'm thinking, than a freezer at Heathrow. Better to keep typing and hope that Death, like the Nobel Committee, is busy looking for someone else to pluck.

"You've got more than you need," Roth says by way of farewell. "Don't fuck it up."